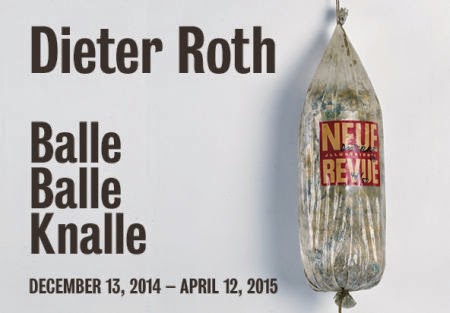

DIETER ROTH

BALLE BALLE KNALLE

Kunstmuseum Stuttgart

Kleiner Schlossplatz 1 - Stuttgart

December 13, 2014–April 12, 2015

The Swiss artist Dieter Roth (1930–1998) is one of the most influential creative minds of the 20th century. His rich and multifaceted oeuvre offers an exemplary illustration of the blurring of the boundaries between the arts—the process in which, in the 1960s, artists left the traditional forms of expression, painting and sculpture, behind in order to explore new genres such as the multiple, performance art, body art, and the multimedia installation. Previous displays of Roth’s work have devoted too little attention to a central feature: the involvement of language and literature in his art, which runs like a common thread through almost all parts of his oeuvre.

Roth, in fact, considered himself a writer first and foremost; not unlike Marcel Broodthaers, he saw his production of visual art as a way to support himself as he wrote. Throughout his life, Roth wrote lyric poetry, essays, plays, and diaries, edited journals, and worked as a publisher. For evidence of how closely his literary work was intertwined in his own mind with his wider creative output, we only need to look at the 26 volumes of his Collected Works, where poems appear mixed freely with prints.

The very roots of Roth’s art lie in literature. As a teenager, he wrote his first lyric poetry; in the 1950s and 1960s, concrete poetry and Fluxus inform his work. He would subsequently distance himself from both movements, but their influences are discernible in Roth’s visual art. In Reykjavík, for example, Roth initially worked mostly on books in which he pursued the further reduction of his concrete poems; the resulting works are considered important antecedents for the medium of the “artist’s book.” Works in the form of objects such as the “literary sausages,” for which Roth pulped books, are likewise based on the principles of concrete poetry, but refract that school’s emphasis on the poet’s linguistic tools through the prism of irony.

In the mid-1960s, the use of perishable materials, the rejection of familiar artistic practices, and the integration of process-based aspects, but most importantly, the playful engagement with words and their various levels of meaning suggest affinities with Fluxus artists such as Arthur Köpcke and Emmett Williams, who were also personal friends of Roth’s. Another aspect that becomes more and more significant in his art is the relationship between language and music, between the word and sound; that is evident in the “Olivetti-Yamaha-Grundig Combo” he constructed in the early 1980s in collaboration with Björn Roth: a contraption involving a typewriter, an organ, and a recording device designed to produce musical renderings of poems and letters.

The exhibition will present significant works from different periods in Dieter Roth’s oeuvre in order to demonstrate the inextricable interconnection between text and image in his art and to show how his work on his literary production and his visual art influence each other. The show’s perspective will also suggest a reassessment of the art of the 1960s, whose profound transformations should perhaps be described not as an “exit from the picture” (Laszlo Glozer), but rather as an “exit from the book.”

BALLE BALLE KNALLE

Kunstmuseum Stuttgart

Kleiner Schlossplatz 1 - Stuttgart

December 13, 2014–April 12, 2015

The Swiss artist Dieter Roth (1930–1998) is one of the most influential creative minds of the 20th century. His rich and multifaceted oeuvre offers an exemplary illustration of the blurring of the boundaries between the arts—the process in which, in the 1960s, artists left the traditional forms of expression, painting and sculpture, behind in order to explore new genres such as the multiple, performance art, body art, and the multimedia installation. Previous displays of Roth’s work have devoted too little attention to a central feature: the involvement of language and literature in his art, which runs like a common thread through almost all parts of his oeuvre.

Roth, in fact, considered himself a writer first and foremost; not unlike Marcel Broodthaers, he saw his production of visual art as a way to support himself as he wrote. Throughout his life, Roth wrote lyric poetry, essays, plays, and diaries, edited journals, and worked as a publisher. For evidence of how closely his literary work was intertwined in his own mind with his wider creative output, we only need to look at the 26 volumes of his Collected Works, where poems appear mixed freely with prints.

The very roots of Roth’s art lie in literature. As a teenager, he wrote his first lyric poetry; in the 1950s and 1960s, concrete poetry and Fluxus inform his work. He would subsequently distance himself from both movements, but their influences are discernible in Roth’s visual art. In Reykjavík, for example, Roth initially worked mostly on books in which he pursued the further reduction of his concrete poems; the resulting works are considered important antecedents for the medium of the “artist’s book.” Works in the form of objects such as the “literary sausages,” for which Roth pulped books, are likewise based on the principles of concrete poetry, but refract that school’s emphasis on the poet’s linguistic tools through the prism of irony.

In the mid-1960s, the use of perishable materials, the rejection of familiar artistic practices, and the integration of process-based aspects, but most importantly, the playful engagement with words and their various levels of meaning suggest affinities with Fluxus artists such as Arthur Köpcke and Emmett Williams, who were also personal friends of Roth’s. Another aspect that becomes more and more significant in his art is the relationship between language and music, between the word and sound; that is evident in the “Olivetti-Yamaha-Grundig Combo” he constructed in the early 1980s in collaboration with Björn Roth: a contraption involving a typewriter, an organ, and a recording device designed to produce musical renderings of poems and letters.

The exhibition will present significant works from different periods in Dieter Roth’s oeuvre in order to demonstrate the inextricable interconnection between text and image in his art and to show how his work on his literary production and his visual art influence each other. The show’s perspective will also suggest a reassessment of the art of the 1960s, whose profound transformations should perhaps be described not as an “exit from the picture” (Laszlo Glozer), but rather as an “exit from the book.”