JOHN CHAMBERLAIN

organized by Susan Davidson

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

1071 Fifth Avenue - New York

23/2/2012 - 13/5/2012

From February 24 to May 13, 2012, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum presents John Chamberlain: Choices, a comprehensive examination of the work of the late John Chamberlain and the first U.S retrospective since 1986. Comprising approximately one hundred works, John Chamberlain: Choices examines the artist’s development over a sixty-year career, exploring the shifts in scale, materials, and techniques informed by the assemblage process that was central to his working method. The exhibition presents works from Chamberlain’s earliest monochromatic iron sculptures and experiments in foam, Plexiglas, and paper, to his final large-scale foil pieces, which have never been shown in the United States. Chamberlain was first celebrated at the Guggenheim in a 1971 retrospective.

“One day something—some one thing—pops out at you, and you pick it up, and you take it over, and you put it somewhere else, and it fits. It’s just the right thing at the right moment. You can do the same thing with words or with metal,” Chamberlain has stated. Fit and choice have rightly become the guiding principles for Chamberlain’s work. His respect for the material’s inherent properties informs the multiplicity of his forms, the simplicity of his process, and the work’s complex underpinnings. The title of the Guggenheim’s exhibition pays tribute to the artist’s process of active selection, or choosing, that is fundamental to his practice.

Born in 1927 in Rochester, Indiana, Chamberlain (1927-2011) briefly studied painting at the Art Institute of Chicago (1951–52), and at the avant-garde Black Mountain College (1955–56), near Asheville, North Carolina, where he credited his time with teachers including poets Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan, and Charles Olson among the greatest influences on his work. He rose to prominence in the late 1950s with energetic, vibrant sculptures hewn from disused car parts, achieving a three-dimensional form of Abstract Expressionism that astounded critics and captured the imagination of fellow artists. An inveterate rebel, Chamberlain also violated the formalist prohibition deriding the use of color in sculpture. He chose to adapt uncommon, recycled materials in his work such as the slick, industrial palette of defunct auto bodies.

Chamberlain moved to New York in 1956, where he developed his particular method of assemblage, first using small found metal parts that quickly became larger welded versions of bent and twisted steel. Although he was originally influenced by the compilation methods of David Smith (who also relied on welding found metal parts), Chamberlain’s work soon showed a preference for voluminous and spatial masses. His astonishing, balanced sculptures stressed the deep volumes and eccentric folds that he managed to achieve by squeezing or compressing the metal and then welding the disparate elements into highly developed, collage-like compositions.

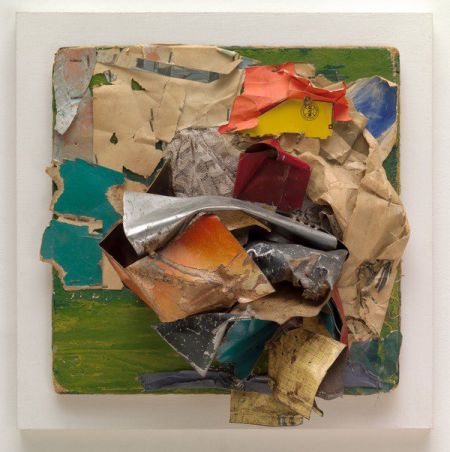

Equally conversant in a variety of materials, Chamberlain had not solely restricted his medium to automobile parts. For a seven-year period beginning in 1965, he returned to painting, using an enamel automobile finish to produce highly glossed, small-format square pictures; he ventured into writing and directing 16 mm films; and, fueled by his interest in science, he began an investigation into unusual materials such as urethane foam, aluminum foil, paper bags, and mineral-coated Plexiglas. Later, printmaking and photography (using a wide-angle camera attached at hip level) entered his artistic repertoire.

In addition to Abstract Expressionism, throughout his career, Chamberlain had been associated with both Minimalism and Pop. His works composed of “crushed automobile parts” in bright colors resonated with America’s fascination with consumer car culture, accordingly aligning him with the contemporary work of many Pop artists whose focus was on the object. On the other hand, for Donald Judd and his compatriots, Chamberlain’s sculptures embodied the neutral, redundant, and expressively structured tenants of Minimalism that sought to remove objectivity, inexpressiveness, and the referential. The attempts to place Chamberlain in such various, conflicting categories acknowledge the artist’s elusiveness and singularity. His tireless pursuit of discovery, his curiosity, and his intuitive process distinguished him as one of the most important American sculptors of our time.

Since returning in the mid-1970s to metal as his primary material, Chamberlain limited himself to specific parts of the automobile (fenders, bumpers, or the chassis, for example). He added color to––or in some techniques, subtracting color from––the found car parts by dripping, spraying, and patterning on top of existing hues to often-wild effect. This liberation and deep exploration of color reference Vincent van Gogh and Henri Matisse, two artists whose color sense he greatly admires. Beginning in the late 1980s, Chamberlain began using the discarded tops of custom vans, cutting them into long ribbons that he left unfurled, crumpled into undulating bands, or rolled into dense rosettes. The scale of his work increased dramatically at this time, aided in part by a significantly larger studio space in Sarasota, Florida, in 1980, and ultimately on Shelter Island, at the far end of Long Island, where he worked until the last days before his death in December 2011.

Over the last three decades, Chamberlain worked in varying ways within his basic artistic equation, but as his work matured, he moved toward more aggressive manipulations of form and color and away from crashed-car renown. Perhaps not intentionally, the deep folds of Chamberlain’s sculptures resemble Renaissance drapery studies that imply the underlying presence of a figure, or conversely, a void. His works throughout the 1990s and first years of the twenty-first century became increasingly volumetric, if not baroque, in their massing of form and vibrant color choice. However, in the last five years, the artist embarked on the production of a new body of work that demonstrates a decided return to earlier concerns. Among the largest works he ever made, these confidently monumental bonfires of metal, with their stacks of mostly horizontal and vertical crushed and rolled metal are drawn from a supply of 1940s and 1950s automobiles. The works’ elegant refinements and exponentially complex renderings exemplify his long-held artistic philosophy, “it’s all in the fit.”

Exhibition Installation

The exhibition encompasses John Chamberlain’s full range of sculptural production and is organized chronologically, spiraling up the Frank Lloyd Wright–designed rotunda. Relief sculptures and assemblages installed on the walls and on the ramps create opportunities to experience the work two-dimensionally as well as in the round. Doomsday Flotilla (1982), a seven-part work of painted and chromium-plated steel, is on view in the High Gallery, and SPHINXGRIN TWO (1986/2010), an aluminum arc reaching up to 16 feet, is installed on the rotunda floor and marks the first time a work from this series has been shown in the United States. C’ESTZESTY (2011), a nearly 20-foot-tall work of painted and chromium-plated steel and stainless steel will be placed along the Fifth Avenue facade of the museum, allowing passersby a view from the street. A foam sculpture carved to resemble and serve as a couch for visitors, which occupied the rotunda floor during the 1971 retrospective, will be re-installed on Rotunda Level 6.

Catalogue

John Chamberlain: Choices is accompanied by a fully illustrated, 248-page catalogue offering a rich and thorough examination of the artist’s work and career. In addition to an introductory essay by exhibition curator Susan Davidson that explores Chamberlain’s early career and underlying scientific approach to his art, the book features a historic overview of Chamberlain’s work by art critic and author Dave Hickey. An essay by art historian Adrian Kohn reviews the scholarly literature produced thus far on Chamberlain’s work and examines the ways in which language is used to describe the artist’s works. In a reflective piece about abstract sculpture, Conceptual artist Charles Ray considers Chamberlain’s influence on younger artists, and Donna De Salvo, Whitney Museum of American Art chief curator and deputy director for programs, considers the artist’s photography in relation to sculpture. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum assistant curator Helen Hsu contributes the first in-depth chronology produced for the artist, including a complete exhibition history, and independent scholar Don Quaintance offers a lexicon providing background and context for Chamberlain’s witty and imaginative titles. The catalogue is available in hardcover ($65) and softcover ($45) editions at the Guggenheim Store or online at guggenheimstore.org, and is distributed to the trade by Artbook | D.A.P and Thames & Hudson.

organized by Susan Davidson

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

1071 Fifth Avenue - New York

23/2/2012 - 13/5/2012

From February 24 to May 13, 2012, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum presents John Chamberlain: Choices, a comprehensive examination of the work of the late John Chamberlain and the first U.S retrospective since 1986. Comprising approximately one hundred works, John Chamberlain: Choices examines the artist’s development over a sixty-year career, exploring the shifts in scale, materials, and techniques informed by the assemblage process that was central to his working method. The exhibition presents works from Chamberlain’s earliest monochromatic iron sculptures and experiments in foam, Plexiglas, and paper, to his final large-scale foil pieces, which have never been shown in the United States. Chamberlain was first celebrated at the Guggenheim in a 1971 retrospective.

“One day something—some one thing—pops out at you, and you pick it up, and you take it over, and you put it somewhere else, and it fits. It’s just the right thing at the right moment. You can do the same thing with words or with metal,” Chamberlain has stated. Fit and choice have rightly become the guiding principles for Chamberlain’s work. His respect for the material’s inherent properties informs the multiplicity of his forms, the simplicity of his process, and the work’s complex underpinnings. The title of the Guggenheim’s exhibition pays tribute to the artist’s process of active selection, or choosing, that is fundamental to his practice.

Born in 1927 in Rochester, Indiana, Chamberlain (1927-2011) briefly studied painting at the Art Institute of Chicago (1951–52), and at the avant-garde Black Mountain College (1955–56), near Asheville, North Carolina, where he credited his time with teachers including poets Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan, and Charles Olson among the greatest influences on his work. He rose to prominence in the late 1950s with energetic, vibrant sculptures hewn from disused car parts, achieving a three-dimensional form of Abstract Expressionism that astounded critics and captured the imagination of fellow artists. An inveterate rebel, Chamberlain also violated the formalist prohibition deriding the use of color in sculpture. He chose to adapt uncommon, recycled materials in his work such as the slick, industrial palette of defunct auto bodies.

Chamberlain moved to New York in 1956, where he developed his particular method of assemblage, first using small found metal parts that quickly became larger welded versions of bent and twisted steel. Although he was originally influenced by the compilation methods of David Smith (who also relied on welding found metal parts), Chamberlain’s work soon showed a preference for voluminous and spatial masses. His astonishing, balanced sculptures stressed the deep volumes and eccentric folds that he managed to achieve by squeezing or compressing the metal and then welding the disparate elements into highly developed, collage-like compositions.

Equally conversant in a variety of materials, Chamberlain had not solely restricted his medium to automobile parts. For a seven-year period beginning in 1965, he returned to painting, using an enamel automobile finish to produce highly glossed, small-format square pictures; he ventured into writing and directing 16 mm films; and, fueled by his interest in science, he began an investigation into unusual materials such as urethane foam, aluminum foil, paper bags, and mineral-coated Plexiglas. Later, printmaking and photography (using a wide-angle camera attached at hip level) entered his artistic repertoire.

In addition to Abstract Expressionism, throughout his career, Chamberlain had been associated with both Minimalism and Pop. His works composed of “crushed automobile parts” in bright colors resonated with America’s fascination with consumer car culture, accordingly aligning him with the contemporary work of many Pop artists whose focus was on the object. On the other hand, for Donald Judd and his compatriots, Chamberlain’s sculptures embodied the neutral, redundant, and expressively structured tenants of Minimalism that sought to remove objectivity, inexpressiveness, and the referential. The attempts to place Chamberlain in such various, conflicting categories acknowledge the artist’s elusiveness and singularity. His tireless pursuit of discovery, his curiosity, and his intuitive process distinguished him as one of the most important American sculptors of our time.

Since returning in the mid-1970s to metal as his primary material, Chamberlain limited himself to specific parts of the automobile (fenders, bumpers, or the chassis, for example). He added color to––or in some techniques, subtracting color from––the found car parts by dripping, spraying, and patterning on top of existing hues to often-wild effect. This liberation and deep exploration of color reference Vincent van Gogh and Henri Matisse, two artists whose color sense he greatly admires. Beginning in the late 1980s, Chamberlain began using the discarded tops of custom vans, cutting them into long ribbons that he left unfurled, crumpled into undulating bands, or rolled into dense rosettes. The scale of his work increased dramatically at this time, aided in part by a significantly larger studio space in Sarasota, Florida, in 1980, and ultimately on Shelter Island, at the far end of Long Island, where he worked until the last days before his death in December 2011.

Over the last three decades, Chamberlain worked in varying ways within his basic artistic equation, but as his work matured, he moved toward more aggressive manipulations of form and color and away from crashed-car renown. Perhaps not intentionally, the deep folds of Chamberlain’s sculptures resemble Renaissance drapery studies that imply the underlying presence of a figure, or conversely, a void. His works throughout the 1990s and first years of the twenty-first century became increasingly volumetric, if not baroque, in their massing of form and vibrant color choice. However, in the last five years, the artist embarked on the production of a new body of work that demonstrates a decided return to earlier concerns. Among the largest works he ever made, these confidently monumental bonfires of metal, with their stacks of mostly horizontal and vertical crushed and rolled metal are drawn from a supply of 1940s and 1950s automobiles. The works’ elegant refinements and exponentially complex renderings exemplify his long-held artistic philosophy, “it’s all in the fit.”

Exhibition Installation

The exhibition encompasses John Chamberlain’s full range of sculptural production and is organized chronologically, spiraling up the Frank Lloyd Wright–designed rotunda. Relief sculptures and assemblages installed on the walls and on the ramps create opportunities to experience the work two-dimensionally as well as in the round. Doomsday Flotilla (1982), a seven-part work of painted and chromium-plated steel, is on view in the High Gallery, and SPHINXGRIN TWO (1986/2010), an aluminum arc reaching up to 16 feet, is installed on the rotunda floor and marks the first time a work from this series has been shown in the United States. C’ESTZESTY (2011), a nearly 20-foot-tall work of painted and chromium-plated steel and stainless steel will be placed along the Fifth Avenue facade of the museum, allowing passersby a view from the street. A foam sculpture carved to resemble and serve as a couch for visitors, which occupied the rotunda floor during the 1971 retrospective, will be re-installed on Rotunda Level 6.

Catalogue

John Chamberlain: Choices is accompanied by a fully illustrated, 248-page catalogue offering a rich and thorough examination of the artist’s work and career. In addition to an introductory essay by exhibition curator Susan Davidson that explores Chamberlain’s early career and underlying scientific approach to his art, the book features a historic overview of Chamberlain’s work by art critic and author Dave Hickey. An essay by art historian Adrian Kohn reviews the scholarly literature produced thus far on Chamberlain’s work and examines the ways in which language is used to describe the artist’s works. In a reflective piece about abstract sculpture, Conceptual artist Charles Ray considers Chamberlain’s influence on younger artists, and Donna De Salvo, Whitney Museum of American Art chief curator and deputy director for programs, considers the artist’s photography in relation to sculpture. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum assistant curator Helen Hsu contributes the first in-depth chronology produced for the artist, including a complete exhibition history, and independent scholar Don Quaintance offers a lexicon providing background and context for Chamberlain’s witty and imaginative titles. The catalogue is available in hardcover ($65) and softcover ($45) editions at the Guggenheim Store or online at guggenheimstore.org, and is distributed to the trade by Artbook | D.A.P and Thames & Hudson.